Disability & Cinema

Chapter Two: Archetypal or Stereotypical

'I am not a human being, I am an animal.'

The Penguin (Danny DeVito) in Batman Returns (Tim Burton, US, 1992)

In this chapter I shall explore and reveal how different films about disability portray disabled people either archetypally or stereotypically. The chapter starts with a close textual analysis of A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg in arguing that it represents disability archetypally rather than stereotypically. It then moves on to demonstrate how impairment is represented stereotypically in the other core films of the thesis, demonstrating the nuances of each form of representation as it proceeds.

The Archetypal

A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg, from a disability perspective, is a film which advocates the segregation and the creation of a formal euthanasia programme for people with severe or congenital disabilities. It legitimates its exploration of disability with a supposedly intellectual debate under a facade of balance. For example, when one character argues for mass euthanasia and another states categorically that she means 'the gas chamber', the first replies: 'that makes it sound horrid'. The implication is that from her perspective the gas chamber for disabled people is not horrid as a form of progressive and necessary social policy (a perspective that the film supports). Surprisingly though, the disabled character is not portrayed stereotypically but prototypically and mythically: a representation that has no doubt of its own universally applicable truth and validity.

Dyer, in an essay in The Matter of Images (1993[a], p.13), makes it clear that stereotypes are historically and culturally determined and that they define social types. To be more specific, they define the limits of social reality, order and control and the parameters of normality for us (the normal), in comparison to them (the abnormal). Dyer argues that if such 'types' are seen as universal and eternal then they are archetypes. Equally, archetypes are the matter of myths, and it is my contention that the Joe Egg character in A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg is an archetypal character: archetypal because she is shown as an ahistorical truth that represents a social group seen as a universal and constant truth beyond rational explanation. It is still a creation but it is constructed in intent and meaning as an archetypal truth outside of any culturally specific influences. Archetypes are no more nor less 'true' or 'false' than stereotypes. The point is that they are utilising a different set of narrative forms and / or cultural beliefs.

This is not to say that Joe Egg is a universal and eternal truth that represents her 'type' truthfully; the opposite in fact: Joe Egg exists as a stereotype doe, a socially mediated construction. The difference is in the manner of representation. The narrative is not about defining the character Joe Egg within the film since she is so self-evidently abhorrent that this requires no elaboration. The point is to discuss - or more precisely, argue - its own agenda: what we should do about them. Joe Egg - the character - is quite literally speechless. She has to be, because to have given Joe Egg a voice would have put into doubt the whole point of the drama; it would have meant that she herself would have had a voice to be listened to. Giving Joe Egg a voice would have made her a stereotype rather than an archetypal or mythical character. The process of stereotyping by giving the disabled character a voice can be seen at work in Whose Life is It Anyway? (a film examined in detail later in the thesis).

A personal anecdote demonstrates my point. I went to a revival of the play of A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg and attended a pre-performance discussion with the author (who also wrote the film's screenplay) at The Everyman Theatre in Cheltenham in 1994. It was a small group and I made it obvious to both the chair and the author that I wished to ask a question. Sadly, they were not going to let me speak because my very presence - as a participating disabled member of society - nullified the philosophy and point of the play. I did not persist despite the constant references to the better 'facilities for people like that' (people with cerebral palsy) nowadays. The irony of the situation was that I was not going to challenge the ideology of the play in the least; I just wanted to know whether the author felt the film to be a more perfect version of the play.

In the first scene in which the audience is shown Joe Egg, the spectator is left in no doubt that she is a symbol of all congenitally disabled people used as a prototype to enact the archetypal function of her role in the myth of the inferiority of Otherness. The camera is focused upon a door handle that is pushed towards the camera, which goes off-screen left, and it reveals the arrival, in medium close-up, of the emerging figure of Joe Egg. Joe is slouched on her detachable wheelchair shelf, as if asleep, with a pillow under her head to demonstrate that this is no temporary aberration but the constant reality of her existence. To emphasise the point, Joe Egg's eyes are open; thus she is not represented as a sentient being but merely an anoetic body.

A conversation takes place between the mother (Sheila) and the father (Bri), with each answering their own questions to Joe Egg, clarifying the point that she does not, and cannot, indulge in conversation, intelligent or not. Bri says to Joe Egg, off screen, with the camera solely on Joe Egg: '[H]ome again: safe and sound'. This is an opening gambit on the welfare of the disabled - safest at home - but the irony soon becomes apparent as Bri takes it upon himself in the narrative to kill Joe Egg for the benefit of all concerned. It is this infanticidal quest that makes A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg aspire to truly mythic status. Bri, we are shown, is a good man who wishes to bring love and joy and peace into the world: he is a secondary school teacher. Thus, he has chosen the path of a vocation and not the sordid route of commerce (as his friend Freddie, in comparison, makes clear later on in the film). Equally, the constant sexual fantasies that Bri indulges in about Sheila, through inter-cut shots of a naked Sheila draped in white silk or lace, also leave us in no doubt that this is a man of passion who still deeply loves his wife after ten years of marriage.

Soon after this initial meeting Joe Egg is left alone with Bri. Bri then sits in a rocking chair, by the side of her, and begins to rock backwards and forwards. This is a medium close-up shot of Bri that pans left and right as he goes to and fro. Upon each rock forward, pan to the left, Joe Egg is seen laying face down on her pillow on her wheelchair shelf in an equal medium close-up. As Bri rocks he talks:

[W]hat's that? You sat by the driver. There's a clever girl. Saw the Christmas tree eh? And the shops lit up. What was that? Saw Jesus. Where was he, eh? You poor softy. (Joe Egg makes a moan like a baby, or animal, that is unconscious.) I see.

In the background of this shot, at the very end, we see Sheila come in from the kitchen door. We cut to a medium shot of Sheila, which pans to watch Sheila walk to Joe Egg, lean over her and kiss her on the head. At which point she remarks: 'I'm lonely she says'. To which Bri retorts, as if it is Joe Egg who is speaking: 'Mad but lonely'.

The mise en scène of having Joe Egg come in and out of the rocking shot clearly displaces Joe out of the harmony that the scene had hitherto implied. The combination of jarring visuals with the fact that as Bri talks he does not even look at Joe leads one to conclude that breaking point for Bri has been reached. As Bri’s tone is one of monotonous routine (the implication is he that has obviously had this one-sided conversation thousands of times already and is getting tired of it) the point is subtly reinforced. A breaking point has been reached for Bri, the scene indicates, due to the strain that Joe and her abnormality are putting upon the family. The strain on the eye of the visuals, which are particularly jarring if you consider that they are close-ups with fairly rapid pans from left to right and back again, are particularly effective in reinforcing the point. Equally, the nature of the dialogue ensures that the 'reality' of living under such a stressful situation is seen as intolerable.

As the story takes place on Christmas Eve there can be little doubt that the story is symbolic of the stagnant morality and alienation of modern life. Joe Egg's grandmother, later in the film, even talks about the 'bad taste' of bringing religion into Christmas. A statement which, by extension and intention, metonymically comments on the condition of Joe as caused by modernity and a lack of Christian spirit (i.e., Joe’s not being allowed to die a natural, 'good taste', death). Again, this would seem rather tenuous if it were not for the fact that Freddie's wife discusses these matters rather explicitly later in the movie with an intensity that gives her value system a high degree of kudos that the film both validates and supports.

A sense of modern alienation is highlighted both within Joe Egg's character (modernity saved and saves her whereas 'naturally' she would have died) and by all the other characters' reactions and relationships to her (Freddie and his wife are, for example, the epitome of superficiality). Consequently, Joe Egg's character is a symbol of the modern society that has created both Joe Egg as she is and the social inability to deal with the problem of Joe Eggs in general. Though Joe Egg's existence may have been created by modern technological advances, the 'nature' of her condition is not; her condition (impairment cum disability) is thus shown and seen archetypally.

One way in which myth works is through the creation of prototypes of significant characters of its subject, a prototype being the ideal version and representative of a group (which because it is seen as universal and eternal, makes it archetypal rather than stereotypical). As is shown below, in a speech by Freddie's wife Pam, the film does at one point offer a parallel between a list, a whole catalogue, of congenital and acquired impairments, and Joe Egg's condition, thereby making Joe Egg the prototype of the mythically archetypal character of Otherness. If we look at the name given to the Joe Egg character we can see that perhaps subtlety is not Peter Nichols' strong point. We are told that 'Joe Egg', Joe's nickname, is the name Joe Egg's grandmother gives to people who sit around and do nothing. While significant in itself, taken in conjunction with the gender of the name 'Joe Egg' we can see that it is supposed to cover all abnormal people: Joe with an 'e' is the male version of the name, whilst Jo, without an 'e' is the female version. Joe, in the story is female; thus 'Joe Egg' ensures that both female and male 'Jo(e) Eggs' are included. Joe Egg's real name is Josephine - a name synonymous with sexuality since the time of Napoleon – thus the direct contravention of such a sexual myth guarantees that this Josephine is pitied even more.

Joe Egg is not purely a 'type' because she is much more than a cipher: she carries a significant degree of cultural capital within her body. As Barthes (1983, p.117) has written about myths, 'the meaning is already complete, it postulates a kind of knowledge, a past, a memory, a comparative order of facts, ideas, decisions'; and that: 'we reach here the very principle of myth: it transforms history into nature' (ibid, p.129). Thus the 'common recurrences' that Barnes, and the other disability imagery critics, have written about have been the genealogical discourses drawn upon by A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg to create Joe Egg as an archetypal character in the mythic narrative that the film is emulating. Barthes acknowledges the historical construction of the archetype and mythic character whilst seeing that they are much more than stereotypical because of their ability to transcend the apparent influences of contemporary life. Their age and apparent 'naturalness' is seen as 'common-sense' and ensures that they as constructions escape the confines of the much more susceptible stereotype. As Barthes (1983) also writes:

[M]ythical speech is made of a material which has already been worked on so as to make it suitable for communication: it is because all the materials of myth (whether pictorial or written) presuppose a signifying consciousness, that one can reason about them while discounting their substance. (Barthes' emphasis - p.110)

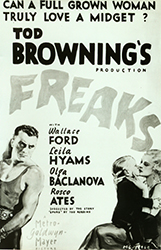

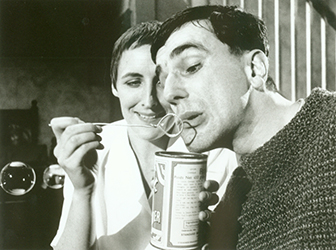

If examined in the light of A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg's drama, this would explain how so much can be interpreted from the presence of Joe Egg in the narrative despite the fact that she does, and says, virtually nothing. Socio-cultural meaning is explicit within her archetypal symbolism and her represented essence; as Barthes (in general) has pointed out, this has been achieved by discounting its subject’s (her) substance. The disabled body does not essentially reveal the character within it. Mythically, the disabled cinematic body has become a self-revealing meta-language; a meta-language easily understood by the audience and consumers and users of such a language, making the abject view of disability axiomatic. As such, it is a language that requires no translation or elaboration. It is a language developed in films as diverse in subject, genre, period and form as Freaks (Tod Browning, US, 1932), Gigot (Gene Kelly, US, 1962), Kings Row (Sam Wood, US, 1942), Life Begins at Eight-Thirty (Irving Pichel, US, 1942), Mandy, On Dangerous Ground, Sorry, Wrong Number (Anatole Litvak, US, 1948) and The Story of Esther Costello, a language further developed and refined in subsequent films such as Carlito’s Way, Crush, Brimstone and Treacle (Richard Loncraine, GB, 1982), Gattaca (Andrew Niccol, US, 1997), Gummo (Harmony Korine, US, 1997), Hana Bi, The Switch (Bobby Roth, US, 1993), Touch (Paul Schrader, US, 1997) and many more.

Joe Egg's character is archetypal in construction because of her supposedly universal and eternally constructed nature, and truth, of impairment as disability; thus she is a character in a supposedly mythic tale; none the less socially constructed, but mythic all the same. Joe Egg does not label herself, nor is she signified by the others around her. It has already been done for her in the last two thousand years (Hevey, 2000). Barrett (1989, p.20) has written: 'archetypes [ ... ] refer to the chief or principal types, which are not necessarily the original ones', and there is no sense in which Joe Egg's character is an original (that Hitler's treatment of people like her in the past is mentioned later in the film ensure that she cannot be seen as the 'original'), but the portrayal of Joe Egg is given as prototypical for her (arche)type: the congenitally abnormal.

When Hitler's treatment of the disabled is mentioned, both as a point of view and as specific to another era, Joe Egg is further restricted to being an archetypal character; especially if we consider Barrett's point (1989, p.13) that: 'the universal aspect of [an archetype's] character [is believed to] transcends any particular [ ... ] society', the word believed being the key in the above quote. The whole point of the film, and play, is not to debate the relative worth of the disabled but to challenge any, or all, society's treatment of them. Thus, the argument from Pam, Freddie's wife, to put them in gas chambers places Joe Egg and the other key characters in the sphere of being archetypal players in a mythic tale. As Rushing (1995) has written:

the cultural expression of a myth responds to historical and political contingencies and may appropriate archetypal imagery, consciously or unconsciously, for rhetorical means - that is, to further the ends of a particular person or group of people or to advise a general course of action. (p.96)

The 'particular person' in this instance is the author. It is significant to note here that Peter Nichols himself had a daughter with severe cerebral palsy and is quoted as saying that: '[W]e put our child in a home, which of course is what the parents in the play should have done' (Editor, 1972, p.358). The political mythologising nature of A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg is encapsulated by Rushing (1995) when she writes that:

[I]t is when myths are unconsciously lived that they lean to regressive wish fulfilment or take on a sinister cast. (p.96)

The personal passion with which A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg is written makes the film a politically motivated piece of rhetoric that passes itself off as reality (until those it depicts as ‘useless eaters’ challenge it). Martin and Ostwalt (1995) make another point about mythic tales in contemporary cinema that is equally applicable to this film, when they write that:

Myths narrate an encounter with the mysterious unknown, with terrifying or awe-inspiring or enchanting Otherness. They do so by describing a sacred place and time, by portraying the quest of a hero, and by probing universal problems of human existence and belief. Mythic films do the same. (p.69)

They continue to write that mythic heroes usually go on a quest and that they strive:

towards a greater insight and freedom or to better the conditions of others. In many versions, the quest takes the hero from a state 'of psychological dependency' to a condition 'of psychological self responsibility'. (p.70)

Joe Egg's father, Bri, fulfils Martin and Ostwalt's criteria for a mythic tale hero. When combined with the fact that the time of the scenario is the 'sacred' time of Christmas and the 'sacred' place is within the family home A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg's narrative can easily be read as mythic in intent. Also, the film is explicitly about Bri's struggle to free himself from an alienating dependency upon his wife and child. In one of the opening scenes of the film, when Bri first arrives home from school, he attempts to indulge in some form of sexual foreplay with his wife Sheila. It is a long shot of the two of them on a couch: Bri puts his hand up Sheila's blouse, to start with, and then, after she has pushed him off, he immediately returns to put his hand up her skirt. At which point Sheila pushes him off again and they indulge in a little aggressive banter which goes as follows:

Sheila: What's the point in starting now. Joe's home in a minute.

Bri: Well?

Sheila: Well! She's got to be fed, bathed, exercised. You know that.

She can't wait can she.

Apart from the obvious implication that having a disabled child makes a parental relationship somewhat frigid, we have the father, Bri, appearing 'psychologically dependent' by his infantile behaviour. When Sheila pushes him off and tells him that they must stop, as Joe is due home, Bri sits up and moves to the furthest point away from Sheila on the sofa. Bri then adopts the attitude that is the standard pose of an aggrieved adolescent who can't get his own way. That the foreplay - fumbling on a sofa - is as equally indicative of awkward infantile or adolescent behaviour serves to reinforce the idea that Bri has become emotionally weak and as equally dependent upon Sheila as Joe Egg is physically. That his name - which one presumes is Brian - has been halved, leads us to conclude that he is an emasculated male (half-man); emasculated by his acceptance of what is, in the logic of the film, a deformed version of the family. When we hear that Bri and Sheila cannot have any more children, the idea that Bri is the victim of emasculation is left in no doubt. Thus the film becomes a mythic journey, Bri’s journey, as Martin and Ostwalt have demonstrated in their definition, towards greater insight, freedom and psychological independence for himself and his wife. Consequently, Bri tries to kill Joe Egg by leaving her out on a cold night and when that fails he leaves – quite literally, as it is a journey on a train - to start a new life. Not that this is shown as a selfish quest: the closing scene of Bri on the train to London, lying on a train seat in the foetal position, is ambiguous enough to suggest that he is not being selfish but 'cruel to be kind'. Bri’s actions will force Sheila to face her psychological dependence upon what is, symbolically, a dead child, as much as they will make Bri face his own situation. Bri, in true mythic style, is being unselfish rather than selfish.

Joe Egg's physical being, which does little except lift an arm every now and again whilst having an epileptic fit (and sneezing once) makes the representation of such an individual appear as one of the living dead; worse even, the suffering living dead. When a joke about putting the cat down is taking place as Joe Egg is having a fit, the irony is adeptly used to equate Joe's condition with that of a suffering animal. The joke takes place during a shot that is very staged and theatrical, a tableau of a death scene. All the characters of the film are in the shot with Joe forefronted, lying on a bed, with the rest of the cast leaning over her in positions that indicate their importance to the plot. The joke maker, the grandmother, is furthest from Joe, making her dialogue and Joe's presence the key signifiers of the shot. Creating a mise en scène that easily nullifies Freddie's subsequent piece of dialogue that the idea of putting something (one) down applies to the cat (an animal) and not Joe (a human being). The point is that Joe is an animal as she is not, in the view of the film, capable of thought or pleasure or movement.

Sheila is also an archetypal character (see Rushing, 1994, for a greater elaboration on the feminine archetype) in that her archetypally constructed ‘mother instinct’ is absolute; this is no Eve to be tempted by sexual promiscuity or immediate pleasure (as in her past). Sheila’s dedication is total and she will, as she says - in extreme close-up to emphasise the strength of her conviction - look after Joe until one of them dies. Such a characterisation is seen as a transformation from her previous lifestyle: Bri and Sheila have a love scene, one that is Bri's recollection in flashback, informing us that prior to Sheila’s marrying Bri she was extremely sexually active. Thus, the transformation of Sheila acts not only, in the first instance, as an ideal role model but also as a morality tale of the dangers of 'promiscuity' and sexual activity during pregnancy: one's children will bear the sin of their parent(s).

The point about trying to demonstrate that not only Joe, but also Sheila and Bri, are portrayed as archetypal characters in a mythic drama is to clarify the fact that the manner in which other characters are represented can affect the way in which the central character is seen. Thus, I am not arguing for Joe Egg to be seen as a mythic symbol in isolation, but as a member of an ensemble that plays together to create a highly charged moral, and seemingly universally applicable, tale which the film’s makers articulate as being true and valid. Although the film’s makers may think of the film in that light, it is as socially constructed, and culturally mediated, as any other drama or representation. It is a theorisation of this film that makes the term 'regressive wish fulfilment' equally as applicable to this drama as it is does to any Carry On (Gerald Thomas/Ralph Thomas, GB, 1959>1992, generic) film. The only difference, apart from content, is the stage-like mise en scène that is used throughout to give the drama intensity and a claustrophobic atmosphere that gives it an illusion of verisimilitude.

We are told about Sheila's pre-marital sexual activity through a recollection of Bri's as he is getting Joe Egg ready for bed. Bri looks straight at the camera - at the audience - after saying 'I tell you' to Joe, and repeats: 'I tell you'; thereby leaving the viewers of the film in no doubt that the film is aimed at them. Thus, the film makes it clear that this is an educative drama specifically aimed at us, the audience. As these recollections are about the previous promiscuity of his wife - the idea that God has punished them for making blasphemous comments – as well as the dangers of smoking and sexual activity during pregnancy, the intended meaning of the film is clear to the audience. The film creates a narrative structure clearly implying that the question of Joe Egg's state of being is a question of personal, religious and moral philosophy applicable to us all.

I shall now conclude this first section of the chapter by examining in detail the two main monologues by the mothers in the film: Sheila, and Pam, Freddie's wife (Sheila and Bri's best and oldest friends). It is an examination that reveals the narratives as mythic and archetypal rather than merely stereotypical. Sheila's major monologue, which demonstrates her ‘motherly instincts’, actually follows on from Bri's own reminiscences that have just been discussed. The closing scene of Bri's recollections occurs when Bri and Sheila have gone to church to see what the vicar thinks. He offers the usual platitudes about the abnormal not pleasing God, but he also offers a potential cure through baptism. He tells them of another child who was similar to Joe Egg but who can now 'tap-dance'. To ridicule all the characters in his recollection, cum fantasy and flashback, Bri plays them all himself: i.e., parodying a vicar by having him sing and dance Shirley Temple tunes. At the end of the scene with the vicar, Sheila looks at the camera and starts to talk and, after a few lines of dialogue, there is a cut to a close-up of Sheila looking into a mirror, still straight at camera, revealing to us her innermost feelings. Bri and Sheila's fantasies / recollections and realities thus merge, repeatedly, into and out of one another such that they emphasise the disorientation of their lives caused by the arrival of abnormality. Sheila puts it thus:

[T]he vicar was a good man. But Bri wouldn't let me do [the baptism]. I join in these [fantasy re-enactments of the past] to please him. He hasn't any faith that [Joe's] going to improve, whereas I have you see. I am always hopeful. (Cut, here, to Sheila looking in mirror at camera.) Always on the lookout for some improvement. One day when she was - what? - about 12 months old (at which point the camera moves in ever so slightly to concentrate on Sheila's eyes filling with tears), I suppose she was lying on the floor kicking her legs; I was doing the flat. I'd made a little tower of bricks - plastic bricks - on a rug near her head. I got on with my dusting and when I looked again I saw she'd knocked it down. I put the four bricks up again and this time watched her. First her eyes, usually moving in all directions, must have glanced in passing at this bright tower. Then the arm that side began to show real signs of intention (a pause as Sheila wipes tear from eye) and her fist started clenching and spreading with the effort. The other arm - held here like that (Sheila touched her shoulder with her hand) - didn't move. At all. You see the importance - she was using for the first time one arm instead of both. She'd seen something, touched it and found that when she touched it whatever-it-was was changed. Fell down. Now her bent arm started twitching towards the bricks. Must have taken - I should think - ten minutes' - strenuous labour - to reach them with her fingers [ ... ] then her hand jerked in a spasm and she pulled down the tower. (Sheila pauses, upset, etc.) I can't tell you what that was like. But you can imagine, can't you? Several times the hand very nearly touched and got jerked away by spasm [ ... ] and she'd try again. That was the best of it - she had a will, she had a mind of her own. (She continues to explain that Joe Egg became ill and she no longer tried to knock the tower down.) But look what it meant: she was a vegetable.

At this point the image changes to one of Joe Egg running out of a primary school class and then skipping and singing with her class mates, 'normally'. Sheila's monologue continues on the soundtrack:

Bri's mother's always saying 'wouldn't it be lovely if she was always running about', which makes him hoot with laughter. But I suppose women can't help hoping.

At this point the noise of the school playground becomes audible, and the scene changes to a close-up of a beautiful ten-year-old Josephine skipping and singing: 'Mrs D, Mrs I, Mrs FFI, Mrs C, Mrs U, Mrs LTY' (repeated twice). We then cut back to Sheila at the mirror with Freddie walking in through a door behind her; it turns out she is at her amateur dramatics rehearsal; she has just had an emotional breakdown and been composing herself.

In the first part of the monologue Sheila (Janet Suzman) beautifully captures every emotion, attitude and nuance of a mother's dilemma in having a 'monstrous' child. Sheila’s tears appear at appropriate times; every glance down, and back, at the camera is done with consummate skill and confidence in the representation of the total commitment and emotion of a mother’s love for a child. The camera's unrelenting stare on her ensures that the audience can escape none of the trauma that she is going through. That she ends the whole piece with the phrase that women – the archetypal mother in this case - just ‘cannot help hoping' guarantees that we see Sheila as a desperate woman who is trapped into doing all that is required of her to the extreme. She must stay with Joe Egg until one of them dies because that is what motherhood, as defined by herself and her (our) culture, dictates. The film is not about challenging the worth of impaired people, but about their treatment; given that they are seen as a constant burden, in this case the film is about adjusting to the dictates that archetypes of disability require in relation to motherhood, not in relation to abnormality.

The immediate juxtaposition of Sheila's trauma with the visualisation of her mother-in-law's words that it would be 'lovely if [Joe] was always running about', reinforces the idea of Joe Egg as tragic and a 'useless eater'. The juxtaposition also serves to reinforce the film's overall point that mothers should not have to be so heroic when burdened with such children. Sheila, in investing ten years of hope after the incident of Joe’s knocking over some toy bricks - that may well not have happened or been merely accidental – portrays that which is tantamount, for this film’s makers, to an immoral waste of individual and social time and effort. When one considers that Sheila herself (inevitably) accepts that Joe Egg is a 'vegetable', it is difficult to read the narrative in any other way.

Sheila's monologue defines, primarily for Pam's later monologue, the parameters that constitute a worthwhile person, such as when she states that 'she had a will, a mind of her own'. Thus, as long as that was the case, hope, dedication and perseverance are acceptable. Following this logic, then, those who can be normalised can be valued to some extent: a theme of impairment-oriented films that continues to this day in films such as The People vs. Larry Flint (Milos Forman, US, 19960), The Horse Whisperer (Robert Redford, US, 1998), The Might (Peter Chelsom, US, 1998) and There’s Something About Mary (P. & B. Farrelly, US, 1998).

Once a parent accepts, as Sheila herself does, one's child is a 'vegetable', such parental responsibility and dedication is not required. For Nichols, mercy must take its place; that Nichols is confident enough to generalise and provide us with a list of conditions suitable to be classified as 'vegetables' (see below) makes one recall Rushing's point about 'wish fulfilment' and a 'sinister cast'.

The visualisation of the mother-in-law's (Joe's grandmother) wish that it would be 'lovely' if Joe could have been normal acts in two ways. Firstly, the film’s narrative signifies Joe as even more tragic than had been considered before - the very process of comparing an impaired Joe to a normal one makes no other interpretation possible. Secondly, the audience is reassured, in their desire for entertainment, that the child actor playing Joe Egg is not really as Joe Egg is supposed to be: that would be far too depressing and in many ways, bad taste in 'entertainment', however educational in intent (Darke, 1995). In impairment-centred films the opposite is true of what Comolli (1978, p.44) argues about there being 'one body too much' in films about 'real' people. In impairment-centred films, once an audience begins to accept the actor as the 'real' character, via the suspension of disbelief, the drama becomes too depressing. An actor must always be seen to be acting both to provide entertainment and win Oscars (Husband, 1999); after all, portraying disability is one of the rare opportunities to showcase both your own acting skills and the profession as a whole (Darke, 1995).

By having the child actor actually do normal childhood things (skip, hop, jump, sing, and run) the spectator is reassured that the film is to be seen as a mythic exploration of a tricky subject in an entertainment format. It is significant that a similar theatrical device and direction takes place in the play: the little girl playing Joe Egg, just prior to the interval and in order to dispel some of the to depressing fears that the child might actually be like that, appears as a normal girl. In the play the child playing Joe Egg comes on skipping to tell the audience that the second half is not as depressing because Freddie and Pam enter, thus, she will not be so central and is not really disabled. Ironically, given the obsession of advertisements with the ideal (body, lifestyle and pleasure), the television station (Channel 4) on which I saw the film also had an advertisement break there. Interestingly, the stills collection from the film at the British Film Institute, London, also includes a multiplicity of stills, from a fairground scene in which Joe is normal, that do not appear in the released version of the film since they were cut from the final cut of the film.

The length of Sheila's monologue is also unusual (well over three minutes) in that it gives the scene a monotonous intensity not very common on film; it is made to seem to be, while technically it is not, a single long take. That the film comes virtually untouched from the play makes it very static in mise en scène, and indicates the director’s desire and decision to keep the limiting nature of the play intact in order to intensify the film’s drama.

A final point should now be made about how the helping professions' use of various terms plays an equal part in constructing Joe Egg as an archetypal character within the film. When Joe returns from her day-care centre, early on in the film, Sheila and Bri read a letter from its management that explains why Joe has run out of an anti-convulsant drug; they write that there had been a party due to the birthday celebrations of 'one of our kind'. The film is making it specific, and explicit, that Joe is one of a kind and that all who are labelled as she is bear a striking resemblance to one another. What makes this interesting is that in the play (Nichols, 1967, p.18) the same piece of dialogue takes place but the person whose birthday it was is actually named: ‘Colin's’. As a consequence the film further negates any attempt to humanise Joe Egg by objectifying others of her ilk, even outside the narrative confines to which we are privy, through keeping them anonymous.

Giving another impaired character a name could potentially make Joe a human being and, as the whole point of the film is to portray her as archetypal in a mythic tale trying to justify killing her, humanising her (or them) would have been counter-productive. Also, the film in attempting to simplify its point has had to erase nuances that made the play appear slightly contradictory. The film is surely Nichols' perfected version of his own play. The view of the disabled as 'useless eaters' is strengthened in the film to a much higher degree than in the play. That the doctor - though played by Bates as Bri in comic fashion - subsequently calls Joe a 'vegetable' serves only to simplify an already simplified tale.

Pam's monologue, although superficially extreme, is at the crux of the film's philosophy and, I shall argue, it is validated both as she delivers it and by the subsequent unravelling of the narrative. It takes place with only Pam, Freddie and Bri in the room; Sheila is upstairs checking on Joe after Bri has said how he wished he had killed her when he had tried in the past. The scene goes as follows:

Pam: I can't stand anything N.P.A.

Bri: What?

Pam: Non-physically attractive. I know it's awful but it's one of my things; we're none of us perfect. But, old women in bathing costumes, and skin disease and weirdies (something she has called Joe Egg earlier). But I can't help feeling a little on

Bri's side (Bri having earlier expressed a desire to kill Joe Egg). Can you?

Bri: Oh!

Pam: I don't mean the way [Bri] means: everyone doing away with their unwanted mums and things. No. I think it should be done by the state.

Freddie: Hitler was the state.

Pam: I know you won't hear of it, but then he loves a lame dog. You know every year he buys so many tickets for the spastics' raffle he wins the TV set; and every year he gives it to the old folks home. He used to try taking me along on his visits at one time. To the blind, the deaf, the dumb, the halt and the lame, and spina bifida and multiple sclerosis.

Freddie: Not for long.

Pam: One place we went there were these poor freaks with - oh, you know - enormous heads (at which point Pam opens her palms about two feet apart) and so on. And you just feel 'Oh, put them out of their misery'.

Freddie: Darling, this is not the time or the place to talk like this.

Pam: They wouldn't have survived in nature. It's only modern medicine, so modern medicine should be allowed to do away with them. A committee of doctors, do-gooders, naturally, to make sure there's no funny business. And then [ ... ]

(Freddie interrupts).

Freddie: The gas-chambers.

Pam: That makes it sound so horrid, but if one of our kids was dying and they had a cure that we knew had been discovered in the Nazi laboratories would you refuse to let them use it?

Freddie: That's hardly an excuse for killing six million people.

Pam: I love my own immediate family and that's the lot. I can't manage anymore.

Freddie: Then it's time you tried.

At which point Freddie forcibly leads Pam up to see (not to 'meet', that would be to humanise) Joe Egg for the first time.

Pam, as we can see, is the complete opposite of Sheila on the surface. Pam just wants to kill all 'types' of Joe Eggs and put them out of their misery, even though her concluding remark makes it clear that she loves her own children just as much as Sheila does Joe. The difference is in the ability to show - what this film’s makers consider to be - compassion and mercy. Pam accepts she would do what is considered socially unacceptable for her children (benefit from Nazi research), whilst at the same time accepting that enough is enough when it comes to suffering.

Somewhat disturbingly (from a Social Model perspective), the monologues from Pam and Sheila discussed here, out of the play of A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg, have become standard 'O' and 'A' level drama teaching tools and practicals. Pam's monologue proposes the 'gas chamber' as a positive alternative to simply placing a burden on the parents and, as scenes earlier in the film clearly demonstrate, respite care and institutionalisation are seen as equally evil: they merely shift the responsibility from one group to another. The narrative of the film is that the problem of the disabled should be solved, not passed on. When Pam is in full swing the camera follows her from one side of the room to another as she moves from being next to Bri and then next to Freddie, and back again. Also, for almost all of her dialogue (written above), Pam is standing whilst the other two in the room sit, a factor which gives her authority both apparent and real.

All this would be irrelevant if it were contradicted by the narrative as a whole, but Pam is only verbalising what Bri has already said (the film's hero) and what he tried to bring about when he attempts to kill Joe Egg. The attempted murder of Joe Egg fails as an ambulance crew revive Joe Egg. It is the ambulance crew’s resuscitation of Joe Egg that necessitates Bri’s leaving in the end to become 'psychologically self-responsible'. Even when Pam goes up to see Joe Egg, and she comments upon the beauty of the impaired child, she makes the tragedy of impairment seem to be greater. Pam’s entry disrupts Bri’s attempt to murder Joe Egg - whom the only consistently anti-euthanasia character, Freddie, immediately decides to protect by lying to the police – and thus appears to validate Pam's position above all others. Pam’s position is ultimately validated at this point because her system has 'safeguards', unlike Bri's, his is susceptible to the moment of passion (justifiable homicide).

Pam is consequently portrayed as being more significant and morally correct than Sheila. Sheila's monologue shows that she is trapped by her circumstances and is forced to believe in hope. Joe Egg is her daughter and that is what she is supposed to do; she is too close to the situation to mention or discuss it dispassionately. Pam, on the other hand, is dispassionate, perhaps a little too much so, but none the less she appears as an objective observer who at least knows what it is like to be a mother: she does have three children of her own who are described as 'perfect'. When Pam states that she cares for her 'immediate family' she also makes explicit the point that it is the family that matters and not one individual in it at the expense of any of the others. Again, the fact that Bri leaves at the end of the film makes it clear that Sheila has (mistakenly) placed the interests of Joe as an individual above those of the whole family: i.e., Bri and, significantly, Sheila herself.

What is particularly revealing about the drama as mythic tale, and what makes it less of a stereotypical representation of the disabled character, is that the film’s author’s seems to be oblivious to the fact that disabled people act as modern-day guinea pigs for a contemporary medical establishment (Turner, 1992). If, as Pam argues, disabled people were allowed to die, then the vital treatments to maintain the illusion of normality for the ordinary citizen would fall behind. Just as Pam argues that she would happily use the results of Hitler's genocidal policies, she ignores the advances of modern medicine achieved during the routine treatment of disabled people in her own culture (Morris, 1996; Trombley, 1988). Many advances in neuro-surgery, orthopaedics and urology have all been perfected on the disabled. Pam is thus happy to benefit from Hitler's regime but is unaware of medical advances in her own culture achieved through similar actions (Cohen, 1983; Goldberg, 1987). This constitutes a significant point, given that a lack of knowledge is symptomatic of a mythic tale, and a mythic tale is about a higher morality and not dogmatic self-interest within the confines of its own culture.

The exaggeration, and generalisation, of the impaired conditions listed by Pam would, superficially, make the film appear stereotypical in its view of those conditions. Impairments are seen as totally interchangeable and the impaired are seen as having an essentially 'life unworthy of living'. The nature of impairment for Nichols et al is seen as irredeemably pointless; no credit is given for questions of degree, severity or other factors such as class and education.

Sheila and Bri, and Joe Egg, all combine to create a mythic drama of, what the film’s makers believe to be universal significance and eternal relevance, it is such a perspective which makes A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg a representation of the impaired Joe Egg archetypal. This is in spite of the fact that it is a representation none the less socially constructed as a stereotypical representation of the disabled in films such as Whose Life Is It Anyway? and The Raging Moon. Thus, I would argue, Joe's character transcends being a stereotype because of the manner of the narration (mythic) and the specificity of her representation - and not because it is more or less truthful.

The Stereotypical Representation

There are two specific ways in which the stereotypical differ from the archetypal: the first is the process of self-labelling, or self-definition, in the interests of defining the parameters of that specific society's limits on self-identity and in giving it a legitimacy that it would not otherwise possess. Secondly, stereotypes assist in the creation of an in-group and an out-group that is defined within the text itself (not by a morality extrinsic to the film's own sense of reality) in order to create the basis of inter-group relations. Whose Life Is It Anyway? and The Raging Moon demonstrate the process of both practices particularly well. Stereotyping, unlike the use of archetypes, provides legitimacy and identity maintenance where ambiguity exists. The 'commonly recurring' images that appear on our film and television screens indicate that little ambiguity exists in the public consensus. In the case of archetypes, there is no sense in which there is any ambiguity or crisis of legitimacy: the in-group is obviously us, with the out-group them. The in-group and out-group theory also explains the idea(l)s behind the positive stereotype: i.e., when one of them is a bit like us and vice versa; a hypothesis that could partly explain the popularity of a film such as My Left Foot.

If one looks at the self-labelling aspect of stereotypes it is immediately obvious that this is not an issue in A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg. In Joe Egg's case the labelling is done for her by others who do not consider it an issue; the issue in her case is her existence and not its relative worth. Whose Life Is It Anyway? reverses the issue. All the other characters in the film seem, initially, to want to validate Ken Harrison (Richard Dreyfuss) as having a worthwhile life (yet not 'equal'). Thus, he must himself dispel that potentially valid notion to restore the supremacy of normal identity. Ken does this through self-labelling. Similarly, the film does it in the overall narrative by creating a normal past for Ken (and for us to have a visual comparison) to compare with his abnormal present. From the initial onset of abnormality, two identities are created and paralleled: the normal and the abnormal, portrayed stereotypically.

As Dyer (1977, p.29) has stated, stereotypes are one of the 'mechanisms of boundary maintenance'. Ken's latter existence within the bounds of abnormality is paralleled with his previous self to create the boundaries of acceptable abnormality. Equally, as Linville et al (1986, p.198) have said: 'stereotyping is a matter of degrees'; unlike archetypes, which allow very little deviance from their intended meaning, stereotypes are polymorphous even within the same context or text. For example, Ken Harrison's own self-devaluation ensures that normality is not blamed for the differentiation (or boundary construction) with legitimacy achieved by having the abnormal themselves testify to the 'reality' of their abnormality and difference.

In one of the lower-key scenes of the film self-definition and devaluation are laid out very clearly by Ken. In consultation with a therapist who wishes him to view his rehabilitation as the opening to a new life, Ken gives the following retort to the therapist's suggestion that he use a computer to write, rather than dwell on his own inability to sculpt any more. He states:

[D]o you think you change your art like a major in college? I am a sculptor, my whole being, my imagination speaks, spoke, to me through my fingers. I was a sculptor and that was what my life was all about. Now, you people seem to think about survival no matter what. If I'd wanted to write a goddamned novel I would have done it, if I'd wanted to dictate poetry I'd have done that.

Ironically, Ken is talking about identity maintenance, his past and present one, but here it serves to devalue his present one and not discuss identity per se (a key element of stereotyping for both the stereotyped and the stereotyping). Ken is shown in a medium, low angle, shot, in which he is slightly slouched forward with his upper-body held up by a wheelchair strap. Ken is in a manual wheelchair to reinforce the central idea that his identity is now dependent upon others. The ability to create something of one's own choice is also paralleled to the ability to create one's self; now Ken is seemingly unable to do that, he has decided that his life is no longer of value. The low angle of the shot gives Ken the status dictated by his own choice of a future: suicide as a member of the Other.

Ken fulfils two functions: he labels himself as not worthy of life and he creates the boundaries that constitute 'worthy living'. As Dyer (1993, p.16) has written, one of the stereotype's functions is to 'maintain sharp boundary definitions, to define where the pale ends and thus who is clearly within and who is clearly beyond it'. Consequently, in Ken's case, the limits of 'survival no matter what' are defined by those who inhabit the outer-edges of the boundary, with the legitimacy of his view confirmed by its being his own reality. As Dyer has also written, and are exemplified by Ken's testament to his own worth(lessness), stereotypes legitimate the use of a specific entity by defining the position for it that becomes abuse. Whereas Dyer was talking about alcoholism, Whose Life Is It Anyway? is about modern medical practice. A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg is not defining boundaries, or limits, but stating its own views as axiomatic, thereby portraying impairment and disability archetypally - not, as Ken Harrison is, stereotypically.

Ken validates the social process of medical rationalisation and the marginalisation of the physically impaired from the mainstream of society. This occurs primarily because the film's entire narrative is Ken's ultimately successful legal fight to have the right to commit assisted suicide. Stereotypes are ideological in intent and, as Perkins (1979), Dyer (1993[a]) and Oakes et al (1994) have implied, realistic in that they represent the realities of inter-group conflict and identity maintenance. When Perkins (1979, p.155) writes that: 'stereotypes present interpretations of groups which conceal the "real" cause of the groups' attributes and confirm the legitimacy of the groups' oppressed position', she encapsulates their essence as ideological functions. If we apply her analysis to the representation of Ken Harrison's acquired quadriplegia, we can see that Ken is himself confirming the position of an able-bodied society when he confirms that his is indeed a 'life unworthy of living'. The Social Model of disability would postulate that the true cause of Ken's disability is socially constructed and extrinsic to his own body, even though Ken's self-devaluation interprets it as being pathological.

The film's wider ideological position - medical rationalisation and the discrediting of its interpretation of abnormality as valid in its own right - is revealed when the film is analysed from a Social Model perspective to demystify the stereotype. The Social Model interpretation confirms Byars' (1991, p.73) perspective (which echoes and acknowledge Perkins' [1979] work) that 'stereotypes function to reinforce ideological hierarchies by naturalising'; naturalising, in this case, the idea that impairment is pathologically inferior to the idea(l)s of normality. The financing of medical treatment is used in Whose Life Is It Anyway? as a false argument that Ken's preservation is not the appropriate priority for finite resources - the starving of Africa would be better recipients, in the stated view of a black orderly - but such an argument is mistakenly pitted against an emotive issue which, if Ken were allowed to die, would not fundamentally change anyway (such funding would not be re-directed to solving Third World poverty and debt). Ken's self-devaluation is thus made logical as a hierarchical imperative for the survival of mankind and, although ridiculous in the extreme, it is perfectly acceptable in the narrative and to a disablist culture.

Prior to Ken's session with the therapist, there is a flashback to Ken while he is sketching his girlfriend dance, and it is immediately followed by his telling his girlfriend to go and find a 'real' man now that he is disabled. It is a cinematically constructed chronology that ensures that we see without undue ambiguity Ken's dismissal of rehabilitation. The sequencing of the narrative, which repeatedly juxtaposes the good normality to the bad abnormality, insists that we see and share Ken's perspective of his impairment as not only valid but truthful. Such a call to 'truth' is a key element of the stereotype even though this ignores significant information and the interests that are served by such a stereotypical representation of impairment. The same is true of archetypes but the difference, I am arguing, is in the degree of apparent construction in its creation and its subsequent potential reception.

A socio-political problem or situation is often culturally identified through stereotypes: taking on a form in which it can be efficaciously comprehended and ideologically mystified by society. This leads to the development of stereotypes as an ideological attempt to overcome any given socio-political problem – usually for the benefit of the stereotypers, the normal in this case, rather than the stereotyped. On this basis, stereotypes can be classified as culturally specific. Thus, A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg (which argues its philosophy as a point of belief even though it comments upon modernity) is very different to Whose Life Is It Anyway? (a film which is dependent upon modernity for its interpretation even if it also draws on a 'widespread-belief system' [Fraser and Gaskell, 1990]). The self-labelling that takes place in one, and not the other, also seems to support the hypothesis that the process of self-labelling is a key element of a stereotypical representation and not an archetypal one. A good comparison can be seen in A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg, when the label is already there, compared to Whose Life Is It Anyway?, where self-labelling is carried out by the characters within and throughout the text and its drama.

The Raging Moon is equally adept at using self-devaluation as a legitimating process of various ideological agendas and self-labelling as an aspect of its stereotypical portrayal of disability. For example, early on in the film, when Bruce (Malcolm McDowell) is in hospital having collapsed after his brother's wedding, he articulates his own philosophy and that of the film with an absolute and honest conviction. Lying in a hospital bed, unable to maintain his balance, Bruce tells his brother: 'you don't say “ill” to people like me'. He then goes on to tell him that he has got a place in 'a Home for the disabled' (people whom the brother had earlier called 'cripples').

Differentiation is both immediate and final in this instance: Bruce is no longer normal and, as such, must seek isolation in order to fulfil his own devalued sense of self. The ideological hierarchy to be legitimated in The Raging Moon is the segregation of the physically impaired, articulated as the best solution for the impaired / disabled. Bruce chooses it himself and then learns to accept it, which means that his self-denigration is both complete and correct in the context of the narrative. As with Whose Life Is It Anyway?, The Raging Moon is replete with examples of this process: i.e., it is a narrative that inadvertently reveals self-labelling to be part of its impaired characters’ stereotypical representation.

In a further similarity to Whose Life Is It Anyway?, The Raging Moon creates a past normality which is compared with a subsequently impaired life. Some critics and academics have termed this a similar process to ethnocentrism. However, self-labelling and devaluation are slightly different in that the individual, or group, that is negatively stereotyped are one and the same and, more often than not, it is they themselves who make the negative comparison. By having ‘them’ label ‘them’ the legitimacy of the argument is in no doubt. Cripps (1977) aptly writes that:

[M]ost stereotypes emerge from popular culture that depends upon imaginative use of familiar formulas for its audience appeal. Deriving as they do from the familiar, they tend to assert a conservative point of view that speaks of a changeless status quo in which [the stereotyped] take up a well-known position. (p.15)

He later continues:

[T]hus in a society of many groups, stereotypes affirm the values of the dominant group. If these stereotypes become popular, then they easily assure, soothe, and support, thus growing into political spokesmen of the status quo. [ ... ] Even at its most effective, the stereotype may merely reinforce attitudes rather than convert its audiences to new ones. [ ... ] Thus, in a society of many groups, stereotypes affirm the values of the dominant group. (p.18)

Cripps encapsulates the idea of the stereotype acting ideologically in concert with the status quo; the status quo of normality in this case is antithetical to the interests of the abnormal. The stereotypes of abnormality and impairment always confirm the values of normality against abnormality: i.e., the values of the dominant social group. The specificity of stereotypes is that they 'speak of a changeless status quo' that is not a changeless status quo at all; they speak of it as if it were. It is the nature of the representation of the status quo that defines whether or not an image is stereotypical or archetypal. In Whose Life Is It Anyway? the status quo is apparently under threat (due to medical and technological advancements), whereas in A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg the status quo is not under threat, only its behaviour is in question; thus they are (along with all my other points) stereotypical and archetypal, respectively. Both stereotypes and archetypes call upon apparently universal norms and values, which is why so many of each endure. The crux is to what degree they are unintentionally revealed and socially agreed upon, and how they are intended to be received (real or not).

The closing scene of The Raging Moon demonstrates the point. In the final scene Bruce, having been told of the death of his beloved Jill, is being taken back to the Home in the Home’s minibus when he admits that he has 'pissed' himself. The carer tells him that it does not matter, but he insists: '[I]t does matter. Everything matters, if I don't believe that I've had it'. Objectively, this is a fallacy; 'piss' is just 'piss' and as such it does not matter, but subjectively - in the context of a normalising hegemony that sees 'piss' as much more significant - it does matter. Consequently, Bruce validates such a normalising hegemony as a truth that he (and the abnormal and normal alike) must live his life by, thereby making the disability stereotype act as the boundary marker for what is acceptable and not acceptable as normal in this society. The degree to which the issue of boundary marking is significant in any given image (either intentionally or unintentionally revealed) is equally significant in defining the image as either stereotypical or archetypal. The stereotypical is more of an impairment-centred film (defining normality itself) than is the archetypal (which is about defining the behaviour of normal people and not about life as lived by the disabled).

The aspect of stereotypes discussed so far in The Raging Moon and Whose Life Is It Anyway? are elements that define the parameters of what is acceptable and not acceptable; i.e., setting the boundaries of, and for, 'civilised' existence. The point about in-group and out-group aspects of stereotyping is that they define the more specific constituents of group identity in the present, creating for each other their own sense of self-esteem; an identity for both them and us, whichever group one belongs to.

Hamilton and Trolier (1986, p.131) have written of the in-group / out-group situation that 'they are all alike, whereas we are quite diverse'. Of course, the converse is also true, especially in the case of disability. But, following on from Hamilton and Trolier, the in-group (normal people, in this case) perceive themselves as having shared ideas within a broad range of variation, whereas the out-group are seen by the in-group as being virtually homogenous, with no degree of variation. This fits my earlier definition of the archetype in A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg. Here, however, its main applicability is to the more culturally specific question of stereotypes because, as Linville et al (1986) have written:

The more experience a perceiver has with the members of a given social group, the more differentiated the perceiver's representation of the group will tend to be. [ ... ] People will tend to have more highly differentiated representations of members of 'in-groups' than 'out-groups'. (p.182)

In the films under discussion the disabled are the Other, the out-group, and the normal are the in-group; thus a minimum function of the disabled stereotype is to construct an in- and an out-group in order to enable inter-group relations to appear legitimate rather than unequal and socially constructed. I would go further than Linville et al (1986) and argue that people have the capacity to override the knowledge that regular contact with out-group members can provide and to challenge any given stereotype one may have of (O)thers, in order to make it fit (or not) their own stereotypical and archetypal perception of that out-group or its members.

Significantly, a stereotype in its construction does not only define inter-group relations; it also defines intra-group relations. Ethnocentrism plays a very similar role when it places the out-group member in an in-group position and then negatively equates the two; the out-group member is invariably left lacking certain intrinsic aspects of the in-group member that makes the out-group member tragic and / or Other. The key point to be addressed now is how specific characters in The Raging Moon, Whose Life Is It Anyway? and My Left Foot are constructed as out-group members in order to create group boundaries and simultaneously ensure that those individuals stay within that out-group.

In films about impairment / disability the process of in-group / out-group differentiation, via stereotyping, is used more subtly to dictate the definition of what good Otherness is. Stereotypes are not utilised to marginalise further the out-group, but to control the boundaries of acceptable behaviour that they (and those of the in-group) should inhabit. In Whose Life Is It Anyway?, for example, Ken Harrison is given as the good Other in that his actions (suicide) are seen as not only for the benefit of himself but of the community in general. The camera does a pan and tracks over the I.C.U. unit to represent other people with quadriplegia as lifeless. Significantly, Ken is alert and imaginative; Ken is listening intently to a piece of classical music on headphones and enjoying it. In this sequence the film’s makers are cinematically articulating a perspective that sees Ken as the good Other whilst the (generalised) other people in the ward are the bad Other. This is because Ken still wishes to benefit the community, by committing suicide, whilst the rest of the people in the ward exist merely as a burden to society. Ken is still articulate and able to obtain pleasure from a source, thereby making Ken's suicidal tendencies seem altruistic rather than selfish (Armstrong, citing Durkheim, 1990) and appear socially responsible.

Ken is thus different from other members of the homogenous out-group of Otherness, not in order for the film specifically to marginalise that group further (which it does by extension), but to educate its members on how theyshould behave, and to educate the in-group on what we should do to solve the problem of disability / impairment. Ken represents what we should do if ever we find ourselves in that situation: legalise euthanasia, and / or commit suicide. In this way a positive Otherness is constructed alongside a negative one; a positive or negative stereotype depending upon the paradigm applied: it is negative from the Social Model and positive from the Medical Model. Ideal Otherness is, then, ethnocentrically and hierarchically, on a scale of in- and out-group representation, paralleled to normality (in-groupness) to boost the self-esteem and values of the in-group norms. Thus, the stereotype of disability in these films is as much about intra-group relations as inter-group relations; just as Ken's actions are deemed good, so in-group behaviour is modified by creating an etiquette in dealing with Otherness. Stereotypes, it could be argued, enable the stereotyper and the stereotyped to create a clearly defined set of rules by which interaction and inter-group relations can, and cannot, take place in the present. A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg does not attempt this. It argues from beginning to end that interaction (integration) is just not an option: abnormality is essentially abhorrent, as it is an abject essentialist state of being. A Day In The Death Of Joe Egg is not about ameliorating or changing or adjusting a current boundary, but about eradicating existing ones.

The scene in The Raging Moon where Bruce and Jill take a trip out of the institution, with a married couple as their carers, to get an engagement ring, acts in a similar fashion. The two disabled people act as a parody of a heterosexual romance, therefore showing that it need not just be an individual who is stereotyped. The parodying of a heterosexual romance is here the enactment of an ethnocentric stereotype; they are constructed as pathetic by their inability to measure up to a comparative normal heterosexual romance. The two carers are included to portray a normal, sexually active couple. The point about in- and out-group differentiation is that such an aspect of the representation of abnormality and Otherness both defines good and bad Otherness as well as justifying the validation of one group at the expense of another. Jill and Bruce are shown as different to the general mass of the disabled in their Home: no one else is having a relationship or ever leaves the premises. As such, they are used in the narrative as in the similar process of ethnocentricism, to demean themselves using the in- and out-group paradigm. Jill and Bruce define their own suitable behaviour. They subsequently raise the self-esteem of the in-group with its normality validated through Bruce and Jill’s mimicking of it, whilst they themselves are seen as the optimum version of Otherness.

As Dyer (1993) has written:

The role of the stereotype is to make visible the invisible, so that there is no danger of it creeping up on us unawares; and to make fast, firm and separate what is in reality fluid and much closer to the norm than the dominant values system cares to admit. (p.16)

The impaired, the disabled, are often presumed to be culturally invisible - this is one of the mystifying processes of images of Otherness - but images of the disabled (Otherness) abound (Davis, 1995). Only as Otherness are they presented and mystified as being a hidden minority. The disabled as Other are indeed a recurrent image in cinema (Norden, 1994), a realisation that enables us to see Bhabha's point (Bhabha, 1994); he echoes Dyer's quote, above, about groups as Other being as true of disability imagery as they are of the black Other of which Bhabha writes. Bhabha argues that society must constantly re-interpret the Other in order to make solid that which is elusive and prone to slip through the net of cultural purification.

The point must also be made that stereotypers prefer to remain superior to the stereotyped, a process achieved by letting the Other incriminate themselves into Otherness; as Jaspars and Hewstone (1990, p.127) have written: 'in-group favouritism [is] actually far stronger than for out-group derogation'. Such a process increases the legitimacy of the stereotyper - to let them stereotype themselves is always more efficacious.

A scene from My Left Foot aptly encapsulates my point about the in- and out-group aspect of stereotyping. In My Left Foot Christy Brown is encouraged to go to a physiotherapy class with a group of similarly physically impaired people. The scene starts with a long shot, from a very low angle, of the clinic physiotherapy room. The camera then tracks into a medium close-up of Brown and in the background of the shot, once we have reached Brown, we can see other, younger, people with cerebral palsy: 'cripples', as Brown calls them. We then cut to a point-of-view shot from Brown's perspective: a floor level shot, in close-up, of a small boy with an equally severe form of cerebral palsy. The boy has a glazed intellectually 'retarded' look that epitomises every negative culturally popular view of what a spastic is. The shot then changes to one that shows all the atrophied spastic legs and arms of those around Brown on the floor and Brown is horrified and wants to immediately go home. He does, never to return to the clinic. Brown is thus shown as different but special because he then gets his therapy at home and away from all the 'bad spastics'.

The mise en scène detailed above shows Brown seeing other people with cerebral palsy as an homogenous group of cripples with him as different from them (which is supported by his doctor's and family's perspective and actions). As such, it makes him a positive representation for the culture outside the film: the able-bodied audience. The film clearly places Brown within the stereotyped world of the Other and the out-group, yet he is not like them in totality. The film’s makers ideological intent, by their version of Brown, invalidates the invalid; it bolsters society’s weak self-esteem by representing the only 'good cripple' as one who does his / her best to be like the normal. Consequently, Brown acts to facilitate an act of social valorisation of normality. The ambiguity of stereotypes is not that they define explicitly what constitutes the non-stereotyped, but that they define what is stereotypically the Other. Stereotypes define what is not acceptable or agreeable explicitly, and only implicitly that which lies within specific cultural confines (usually laid out within specific texts).

Although Christy Brown's story has certain elements of the stereotypical, as I have argued above, his story (and most 'inspirational cripple' stories) is on the whole much more mythic than stereotypical, with principal characters both stereotypically and archetypally represented. Brown is also represented as an archetype in that he represents the mythic tale of man's struggle against himself and his environment. If we return to Martin and Ostwalt's point about a mythic hero being one who goes on a journey of self-discovery from psychological dependency to self-reliance, we can see that Brown, the 'heroic cripple', is a mythic hero with typically archetypal characteristics: i.e., embodying aspects of the 'human condition'. Consequently, archetypal characters can, and often do, act stereotypically concomitantly. Films such as The Stratton Story, The Miracle Worker (Arthur Penn, US, 1962), A Patch of Blue, The Waterdance (N. Jimenez and S. Michael, US, 1992), Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis, US, 1994) and many others represent the impaired in a similarly dual way that is both archetypal and stereotypical.

In many disability / impairment-centred films the stereotypical ending is either cure or death - the ideological endorsement of medicalisation - and a cure is achieved in these films (My Left Foot and The Raging Moon for Bruce’s character) even though no one is medically cured. The cure is the cure of rehabilitation or normalisation. Death is equally seen as a cure of some sorts, in the other films in question, as it is shown as the ultimate cure of Otherness. Cure, as in the restoration of the impaired self to a conventionally normal self, is prevalent in a high number of disability films, especially around specific impairments such as visual and hearing impairments, but also paralysis. Such diverse films as these are indicative: Afraid of the Dark (Mark Peploe, GB, 1991); Paula (Rudolph Mate, US, 1952); Elmer Gantry (Richard Brooks, US, 1960); Brimstone and Treacle; The Lawnmower Man (Brett Leonard, US, 1993); The Piano (Jane Campion, Australia, 1993); Almost an Angel (John Cornell, US, 1990); and Leap of Faith (Richard Pearce, US, 1992). The cure is often - in the films listed and through normalisation in My Left Foot - a matter of personal will-power and motivation. Thus, these films are inadvertently articulating the ideology of 'the positive stereotype' and 'the negative stereotype' as being linked to individualism. Gilman (1985) writes that:

The bad Other becomes the negative stereotype; the good Other becomes the positive stereotype. The former is that which we fear to become; the latter, that which we fear we cannot achieve. (p.20)

That which we fear we cannot achieve, as demonstrated in these films, is the courage and fortitude needed to be a 'Supercrip'. If we were faced with a disabling condition, what we fear to become is the bad Other of the generalised cripple: dependent and pathetic or one of the living dead. Brown, in My Left Foot, is the good Other as he not only represents the mythic ideal of courage in the face of what is considered a tragedy, but also because he validates normality by striving for it at the expense of validating his own impaired body.

The good Other is a representation that many disability imagery writers have considered to be a positive image in general of disability (see above), but what they are acquiescing to is the 'normative fallacy' (Macherey, 1978). Equally, the notion that negative images are devoid of anything positive is a weak argument. It fails to explain why so many of the stereotyped enjoy – or gain something out of - those bad images of their group. The point about stereotypes and archetypes as reflecting true inter-group relations might help us to appreciate why that is the case; the pleasure could be that as they, the disabled, are discriminated against and feared, the negative image, at least inadvertently, acknowledges and reveals that. Although the images and the ideological bent of the impairment / disability films examined here (and most others) blame the stereotyped, they do at least allow those depicted to acknowledge a significant part of their reality. Such images of disability – in being part of the actual socio-cultural process of disablement - inadvertently acknowledge for the disabled the reality that they inhabit the world of the Other for, perhaps, the purpose of reinforcing the sense of self-esteem of the 'normals'.

The main problem in advocating the positive image - which in the impaired body's case is one of potential normality - is best summed up by Bhabha (1984) when he writes that:

[T]he demand that one image should circulate rather than another is made on the basis that the stereotype is distorted in relation to a given norm or model. It results in a mode of prescription criticism which Macherey has conveniently termed the 'normative fallacy', because it privileges an ideal 'dream-image' in relation to which the text is judged. The only knowledge such a procedure can give us is one of negative difference because the only demand it can make is that the text should be other than it itself. (p.105)

Apart from its being redundant to argue for something to be other than it is, the normative fallacy, as Bhabha has said, argues for a dream that is either not possible or not wanted by many of those stereotyped. Thus, the problem of arguing, in isolation, for the positive image, falls into the trap of accepting the fallacy that there is an ideal manner in which to live and be represented: i.e., as normal. By accepting that the ideal exists, that normality exists, one then becomes implicated in the very process that has been for centuries marginalising and negating the Other: the ultimate disablement of the abnormal. It is not surprising that many disabled people like the idea of the ‘positive’ per se as they, to paraphrase Mary Douglas (1966), perhaps seek to remain on the ‘clean’ side of the pollution boundary.

The ‘normative fallacy’ confirms that impairment / disability centred films, as in the films discussed herein and as a type, act to define the predominant moral and cultural attitudes to Otherness, which, in this case, is the existence of impairment and abnormality. The key is to de-construct the stereotype, the archetype and the mythical symbolism that the disabled are used to represent, to reveal the limits imposed upon what is good or bad. This is not to argue that we should be allowed to be cohabitant with the 'normals' in their illusion, but to discredit that illusion so that the parameters and boundaries are dismantled such that each individual is enabled to be whatever one wishes to be. Consequently, a sphere of freedom would be created for both them and us - you and me - to be whatever we are or wish to be in the future.